Changing ideas

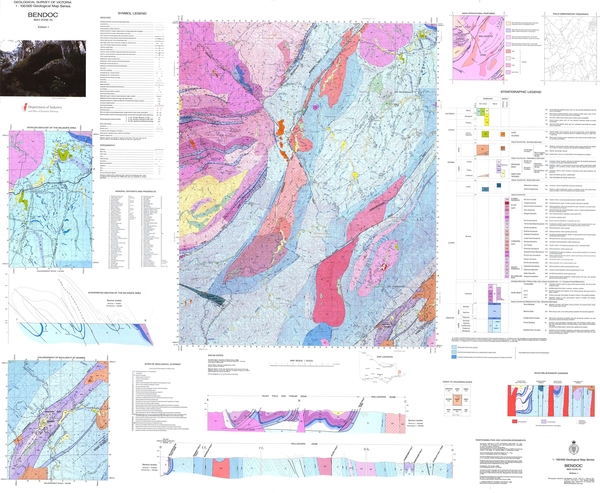

Bendoc 1:100 000 geology (1990)

During the 1980s, the Geological Survey introduced a collaborative approach to mapping, combining the skills of a number of geologists to survey and produce a map. This Bendoc map was the first to be signed by a team, rather than by just one or two geologists.

During the 1980s, the Geological Survey introduced a collaborative approach to mapping, combining the skills of a number of geologists to survey and produce a map. This Bendoc map was the first to be signed by a team, rather than by just one or two geologists.

The 1990 Bendoc map was also the first Geological Survey of Victoria map to illustrate, in an accompanying cross-section, the new concept of thin-skinned tectonics.

More than a century earlier, geologist Norman Taylor had spent an entire year surveying this most easterly part of Victoria, almost single-handed. Snakes, ‘fern jungles’, lost horses, dwindling food supplies, and appalling weather had confounded his efforts. On one occasion, Taylor wrote–

‘I started to go to Eden, to get another man, &c., but, in crossing the Timbillica, got nearly drowned, and damaged my watch, prismatic compass, and note-book, and had to return.’

Another time, ‘being short of stores, we had to live on black swans, cooked in the most primitive manner’. He also ate possums, eels, wallabies and ‘a large black tree lizard’.

Thin-skinned tectonics

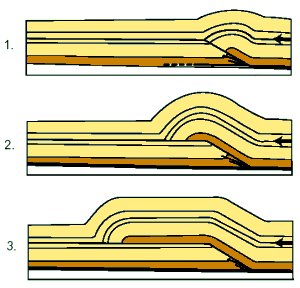

Take one shiny table, add a tablecloth and push it sideways until it crumples into folds and slips across the table top. That’s exactly the way some rocks behave when continents collide, causing massive horizontal pressures. Now replace the tablecloth with horizontally layered rock several kilometres thick and you have what is known in geological terms as thinskinned tectonics (and a broken table).

Take one shiny table, add a tablecloth and push it sideways until it crumples into folds and slips across the table top. That’s exactly the way some rocks behave when continents collide, causing massive horizontal pressures. Now replace the tablecloth with horizontally layered rock several kilometres thick and you have what is known in geological terms as thinskinned tectonics (and a broken table).

Rocks are laid down with the oldest at the bottom and youngest at the top; but in some places thin -skinned tectonics have reversed this pattern, pushing old layers upwards and over younger layers. In Victoria, fossils indicate the relative age of rock layers and show where a disturbance in sequence has occurred.

Thin-skinned tectonics was first identified in the 1960s, but wasn’t found in Victoria until 1982 when geologist Stephen Cox was mapping in the Castlemaine area. Similar structure has since been recognised elsewhere in Victoria.

On Bendoc, Fons VandenBerg used graptolites to explain the way in which the order of rock layers had been disrupted by later earth movements resulting in thin-skinned tectonics.

The diagrams (right) show how the layered rocks slide over a horizontal surface (or fault), then crumple into folds until they reach breaking point. The folds may vary from hundreds of metres across to many kilometres.

Smaller faults break apart the layers that start to pile up on each other. Geologists believe these faults provided the passageways for gold-rich fluids to rise from deep in the earth’s crust to higher levels where they solidified as quartz veins.

Castlemaine - Chewton & Fryers Creek 1:10 000 geology (1994)

The Geological Survey reintroduced detailed mapping of key goldfield areas at 1:10 000 scale in the 1980s.

The Geological Survey reintroduced detailed mapping of key goldfield areas at 1:10 000 scale in the 1980s.

Clive Willman’s maps of the Castlemaine - Chewton and Fryers Creek goldfields use coloured bands to indicate different rock layers. The boundaries between layers were determined by examination of rock structures in the field (in much the same way as Willman’s 19th century counterparts had done), as well as from information conveyed by graptolite fossils about the layers’ relative age.

In the eastern part of both maps, a dramatic geological change is apparent, coinciding with an absence of gold workings.

These two maps were the last produced by pre-digital cartographic methods.

Why re-map areas?

Geological maps become outdated through the emergence of new information and new methods of interpretation.

For instance, on the 1865 Lancefield quarter sheet (A), the sedimentary rocks of the Mount William range are shown as Silurian in age. With the benefit of new fossil information, the 1931 map (B) shows these rocks as belonging to the Cambrian period. This was a significant change as it revealed them to be some of the oldest rocks in Victoria.

The 1991 Kilmore map (C) shows more detailed subdivision of the rock layers in the same area, thanks to updated fossil information and a new interpretation of the way the rocks are folded.

Using the latest information and theories to refine the geological picture of a place reveals details that have eluded geologists in the past. And it is a process that will continue. Even since 1991, fresh light has been shed on the geology of the Lancefield area by the use of airborne geophysics.

Mineral explorers regard new geological maps as essential tools in their search for new deposits. They view geological mapping as the highest priority activity for a Geological Survey.

Page last updated: 02 Jun 2021